But during this period, Elphaba takes up the cause of Animal rights-that’s upper-case A, denoting sentient Animals as opposed to dumb animals. We next see Elphaba at the university, being scorned (at least initially) by the spoiled heiress Glinda, with whom she’s forced to room. (We’re clued in to Elphaba’s real sire later, and it’s a shocker.) For all she knows, it could have been an elf. We meet her first as the deformed infant daughter of a humorless preacher, Frexspar, who tries to convert Munchkinlanders from “paganism” (they believe in the fairy goddess Lurline) to the worship of the “Unnamed God.” Frexspar sees Elphaba’s green skin as that god’s judgment on his failures-or on his promiscuous wife, who’s so addled from chewing narcotic leaf that she can’t remember exactly who fathered Elphaba. In Maguire’s Oz, the real evil is the totalitarian Wizard and, to a lesser extent, Elphaba’s sister, Nessarose, who is known as the Wicked Witch of the East not because she’s diabolically bad, but because she’s angelically good-she’s horrifically holier-than-thou.Įlphaba, by contrast, is self-effacing, a woman who scorns power and claims not not even to have a soul.

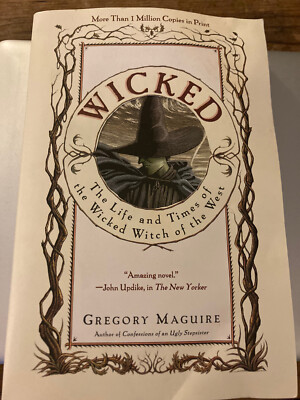

One never learns how the witch became wicked, or whether that was the right choice for her-is it ever the right choice?” By the end of “Wicked,” we’ve seen that it is indeed the right choice for Elphaba, because the particular brand of evil that has defined her for us-hostility to an entrenched authority-is shown to us in a new light. “To the grim poor there need be no pour quoi tale about where evil arises,” the traveler says, “it just arises it always is. Late in the novel, before our pea-green heroine, here named Elphaba, has any idea that she will one day become a witch, she overhears a traveling companion comment tartly on a folk tale. Can we now, as adults, accept a retrofitted history of how an otherwise well-meaning woman went so wrong-to the point of actually sympathizing with her? (And if we can, what unsettling things can we infer about “absolute” evil in our own world?) After all, the Witch is as recognizable to us as any historical tyrant, yet we know her only as evil incarnate, a construction-paper villainess. That it does so by utilizing a character from children’s literature, rather than a historical figure, is part of its genius. For “Wicked” is ambitious it sets out to explore the circumstances that create evil (if evil can even be said to exist). All of which sounds deliciously high camp-like a Charles Busch take on the Oz mythos.īut “Wicked’s” subversive strategy is to suck you in with such juicy pleasures and then hit you with the hard stuff. Gregory Maguire’s “Wicked” reveals the untold history of the Wicked Witch of the West, including her years as the alienated college roommate of a vain, social-climbing beauty named Glinda.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)